Active learning is an approach that encompasses a broad range of teaching strategies that allow learners to become the centre of the learning process. The learning theory behind active learning is called constructivism, which is developed by the psychologist Jean Piaget (1896 – 1980), who stated that learners construct their knowledge based on their experiences, and knowledge cannot be simply imparted to them. Active learning contrasts with a passive approach in which learners are expected to listen to the teacher as he/she talks at them and assumes that the learners will make sense of what is being delivered to them.

A common misconception is that a more lecture-style and direct instruction would prevent active learning from happening. Carefully planned and well-structured direct instruction could be an effective teaching method that supports active learning. It is also important to note that active learning does not mean that the lesson should be filled with activities, especially when these activities do not align with the learning objectives of the lesson.

Most teachers agree that teaching science can be challenging and believe that experiential learning is the best way to teach science. Secondary level science, such as chemistry, involves many theoretical concepts and content-based knowledge. In learning chemistry, ‘chemical literacy’ is based on three representations: macro, submicro, and symbolic representations (Gilbert & Treagust, 2009). Learners are required to make the connections between these three representations in order to understand most of the chemistry concepts.

Scaffolding

Cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner (1915 – 2016) developed the theory of scaffolding, which states that children learn best when adults provide necessary support until they can become independent learners. When planning a lesson, it is important for teachers to identify the parts that might be too complex for learners to understand and provide the necessary support to help them achieve the learning goals. Some ways of scaffolding include breaking down a topic into bite-sized lessons and planning these lessons ‘backward’. This means that the assessment objectives must be identified first, and the lesson is then planned according to these objectives. This can help teachers and learners better visualize what they are working toward. This support should be gradually withdrawn as learners make progress in their learning.

Inductive Learning

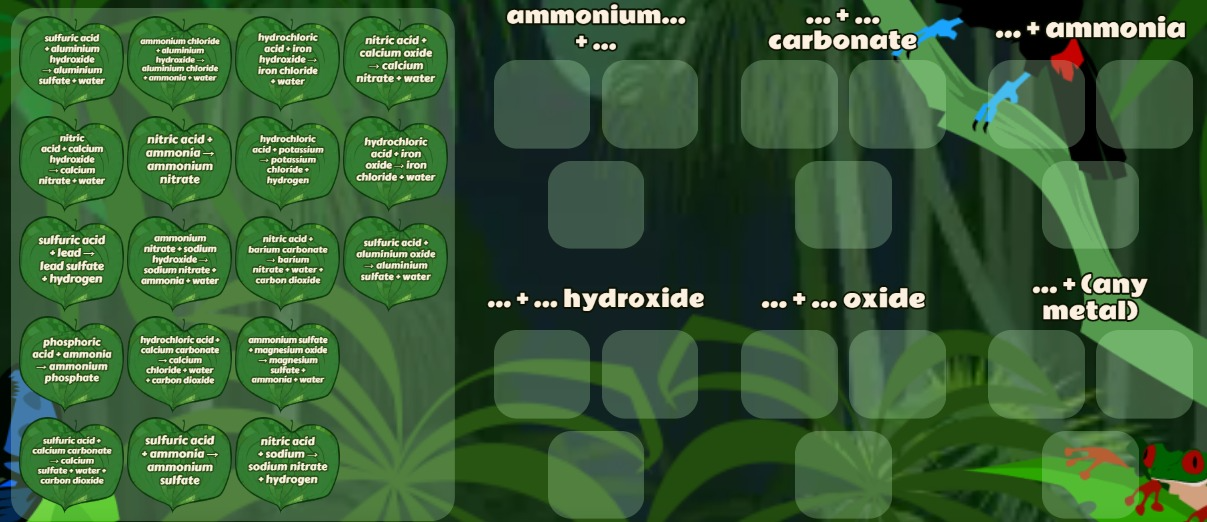

An analysis of the literature suggests that there are sometimes good reasons to “teach backwards” by introducing students to complex and realistic problems before exposing them to the relevant theory and equations (Felder & Prince, 2007). In contrast to deductive learning, where new concepts are first introduced to learners and later applied to solve problems, chemistry involves many chemical reactions and their corresponding chemical equations. In inductive learning, learners are given chemical equations and are instructed to classify these equations based on the type of reaction to which these chemical equations belong. This strategy is also suitable for topics that involve many examples, such as introducing elements in the periodic table.

Matching example equations with general chemical equations

Provocation

Provocation is a great technique if you want to catch learners’ attention at the beginning of the lesson. This technique is intended to provoke learners’ thoughts and interests so that they remain engaged throughout the lesson. There are many ways to use provocation. Some creative approaches involve using one or a combination of emojis and asking the learners to guess the topic and learning objectives of the lesson. It could also entail using a picture or a video related to the real-life applications of the topic.

A provocative question to spark learners’ interest in the topic of rate of reaction

Juxtaposition

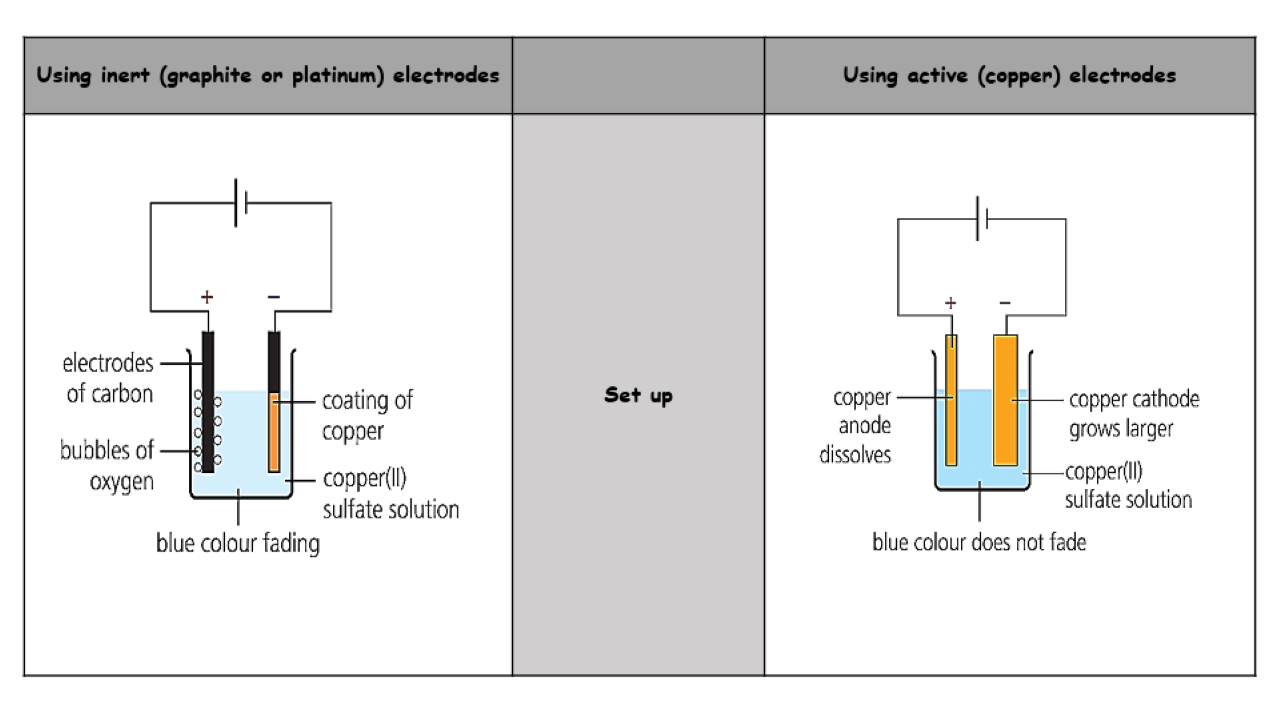

Comparing and contrasting is a very common strategy when learning something new. The strategy is inherent to human nature: making comparisons and identifying similarities and differences. The process of comparison, viewed as a process of structural alignment, constitutes an important route towards abstract conceptual understanding (Gentner & Namy, 1999). Juxtaposition goes beyond merely comparing two ideas. It involves placing two diagrams side by side to better visualize the relationship between two or more scientific concepts. Understanding can be further deepened when the attributes of both (or more) scientific concepts are listed in an organizer, such as using a Venn diagram, a simple side-by-side chart, a top hat, or a Y-shape organizer.

Juxtaposing an active electrode and an inert electrode

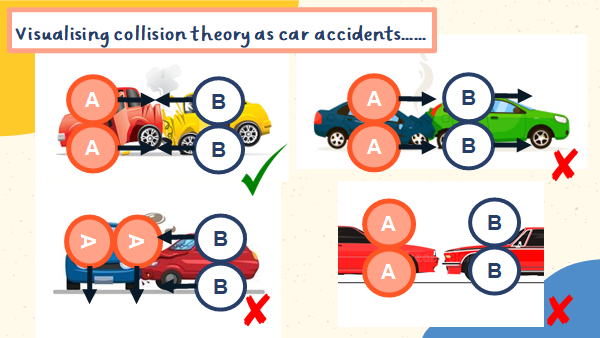

Analogy

An analogy is a great way to introduce new concepts that are difficult to visualize (Orgill & Bodner, 2004). As studies suggest, using analogies is akin to wielding a double-edged sword, as there are ‘good’ and ‘bad’ analogies. Good analogies should be concise and easy to understand. They will also be more effective when the analogy is less scientifically relevant but is easily relatable to learners’ real-world experiences.

An analogical illustration of collision theory

Sketchnotes

Taking notes is an essential and lifelong skill that learners must have in their learning journey. Drawing sketchnotes can be a fun and creative way of note-taking. Drawing words instead of just writing them enhances memory performance, even when the written word contains more details (Wammes et al., 2016). However, not all types of drawings are helpful. A study shows that using organizational drawings instead of representational drawings can help improve metacomprehension (Thiede et al., 2022). An organizational drawing depicts the connections between scientific concepts and helps learners better understand a scientific topic as a whole. Mind maps and anchor charts are simple examples of organizational drawings commonly used in learning science.

A learner’s sketchnotes of the Contact process

Socratic method of questioning

Questioning is a common teaching technique used by every teacher. A good question should promote learners’ critical thinking skills (Chew et al., 2019). It is used to inform teachers about the learners’ progress and is a quick and effective way of assessing learning. It can become an even more effective tool when the questions are used to scaffold learners’ thinking about a complex scientific concept. In the Socratic method, questions are used to draw out the learner’s unexamined assumptions and challenge those biases. It is important to inform learners that they should always think out loud, and there are no right or wrong answers, so that teachers can identify the misconceptions the learners might have. For a more learner-centered and whole-group lesson approach, teachers can employ a Socratic seminar in which the discussion will be more student-led, and the role of the teacher is to facilitate the discussion.

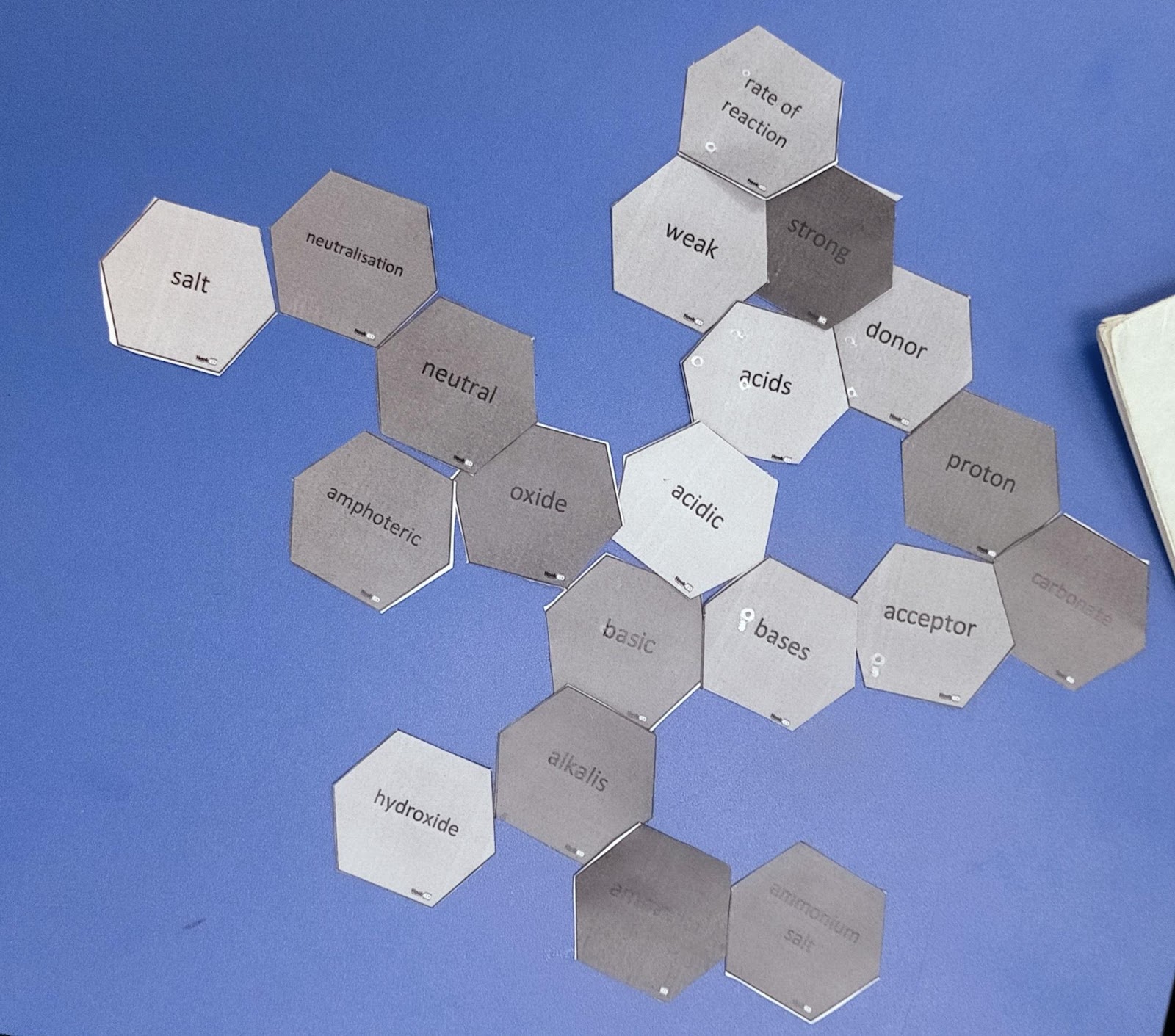

Hexagonal thinking

Hexagonal thinking is a great activity when there are many keywords and key ideas that learners must master in order to proceed in the lesson. This task can be given as either individual work or group work. Different learners connect ideas differently, as the theory of constructivism suggests. Nonetheless, they must be able to justify and explain the connections between the keywords or key ideas. The teacher, as a facilitator, could use this information to provide guidance and feedback to the learners.

Keywords in hexagonal cards joined and done by a group of learners

Reciprocal learning

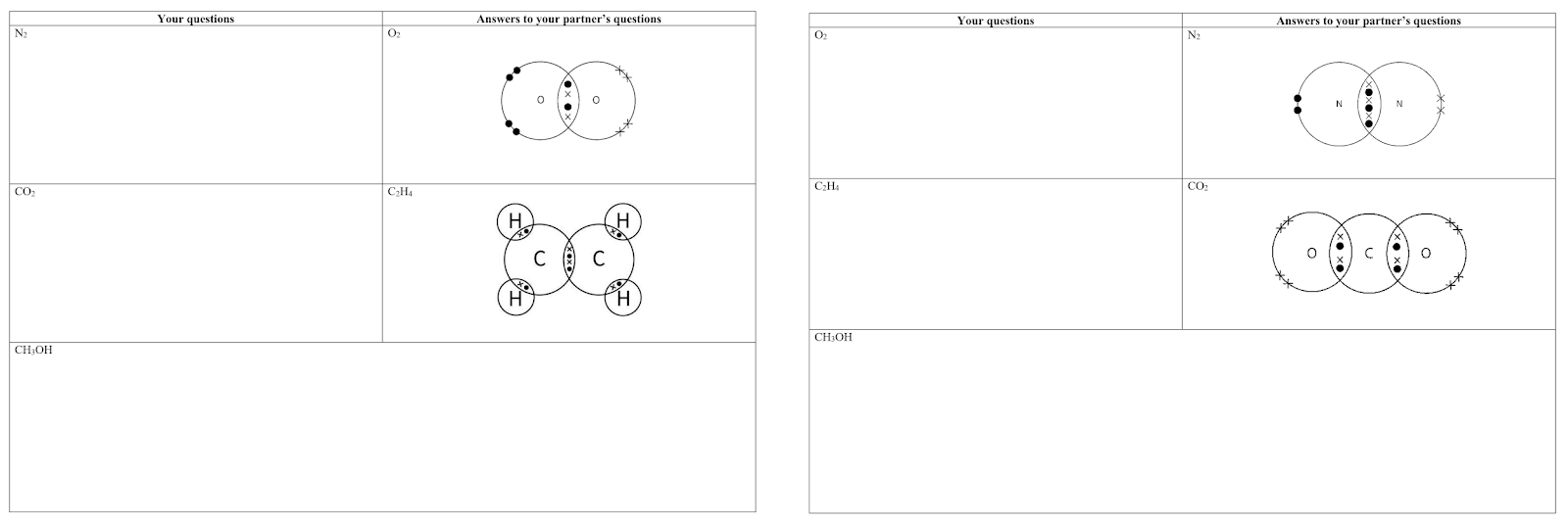

Classwide peer tutoring (CWPT) has been shown to enhance academic performance as it provides opportunities for practice, engagement, immediate feedback, and corrections catering to learners of various learning abilities and challenges (Greenwood et al., 1988). One way of using this approach is through a learner-pairing strategy called reciprocal learning. Two learners form a learning partnership committed to helping each other reach a learning objective. A popular method for employing a reciprocal learning activity is to design two different worksheets with distinct sets of questions. Each worksheet also contains the answers (or even better, explanations for the answers) to the other worksheet. The paired learners take turns assisting each other in solving problems while providing guidance. This strategy has demonstrated that learners are more likely to dedicate more time to tasks when they have a learning partner, develop more positive attitudes toward the subject matter, and become more self-directed and less reliant on the teacher (King-Sears & Bradley, 1995).

A reciprocal learning worksheet to solve cross-and-dot diagrams

Assessment for learning

High-stakes examinations are referred to as assessments of learning (AoL), or more commonly known by another term, summative assessment. Assessment for learning (AfL), on the other hand, serves to help learners make progress in their learning by utilizing feedback from learners to teachers and vice versa. Black and Wiliam (1998) advocated for formative assessment by using assessments to modify learning activities, emphasizing comments given by teachers on learners’ work instead of awarding grades that are less meaningful throughout their learning progress. Topical questions can be tailored to learners’ progress and abilities, and this can be done in the form of something as simple as multiple-choice questions. It’s also worth noting that AfL should be employed periodically, such as at the end of a lesson. However, the effectiveness of it can be maximized when coupled with spacing and retrieval practices. There are ample studies showing that spacing and retrieval practices are two high-impact learning strategies (Carpenter et al., 2022).

While these teaching and learning strategies are arranged chronologically from lesson planning, teaching and learning activities and finally formative assessment, one or more of them can be placed in any order depending on the teacher’s preferences and subject taught.

References

Introduction

Gilbert, J. K., & Treagust, D. F. (2009). Introduction: Macro, submicro and symbolic representations and the relationship between them: Key models in chemical education. In Multiple representations in chemical education (pp. 1-8). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

Scaffolding

Wood, D. J., Bruner, J. S. and Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 17(2), 89-100.

Inductive learning

Felder, R., & Prince, M. (2007). The case for inductive teaching. ASEE Prism, 17(2), 55.

Juxtaposition

Gentner, D., & Namy, L. L. (1999). Comparison in the development of categories. Cognitive development, 14(4), 487-513.

Analogy

Orgill, M., & Bodner, G. (2004). What research tells us about using analogies to teach chemistry. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 5(1), 15-32.

Sketchnotes

Thiede, K. W., Wright, K. L., Hagenah, S., Wenner, J., Abbott, J., & Arechiga, A. (2022). Drawing to improve metacomprehension accuracy. Learning and Instruction, 77, 101541.

Wammes, J. D., Meade, M. E., & Fernandes, M. A. (2016). The drawing effect: Evidence for reliable and robust memory benefits in free recall. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69(9), 1752-1776.

Socratic method of questioning

Chew, S. W., Lin, I. H., & Chen, N. S. (2019). Using Socratic questioning strategy to enhance critical thinking skill of elementary school students. In 2019 IEEE 19th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT) (Vol. 2161, pp. 290-294). IEEE.

Reciprocal learning

Greenwood, C. R., Delquadri, J., & Carta, J. J. (1988). Classwide peer tutoring. Seattle, WA.

King-Sears, M. E., & Bradley, D. F. (1995). Classwide peer tutoring: Heterogeneous instruction in general education classrooms. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 40(1), 29-35.

Assessment for learning

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Granada Learning.

Carpenter, S. K., Pan, S. C., & Butler, A. C. (2022). The science of effective learning with spacing and retrieval practice. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(9), 496-511.

Keele Chin is a science teacher at Axcel International School, Puchong, Selangor. His pedagogical approaches include active learning using various teaching and learning strategies and methods, questioning techniques, technological and web-based learning tools, experiential learning, and timely assessment as and for learning.