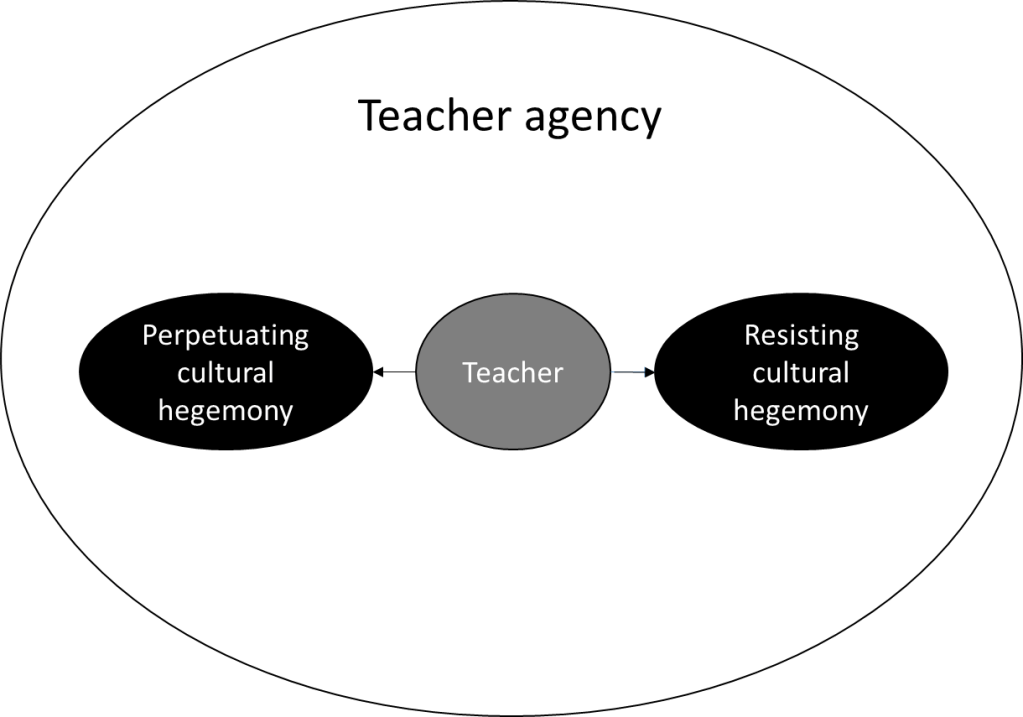

Teaching, as a fundamental pillar of societal development, possesses the power to shape minds and influence perspectives. In this dualistic nature, teaching can act as a mechanism that perpetuates cultural hegemony and acts as a form of resistance to prevailing power structures. In addition, what needs to be taken into account in this dynamic is the concept of teacher agency—the capacity of educators to actively shape and influence the learning environment. By considering this dual nature of teaching, teacher agency involves not only making curriculum choices but also navigating the dynamic interplay of cultural, structural, and material factors. This essay explores how teaching, enabled by the ecological model of teacher agency, can contribute to the perpetuation of cultural hegemony and simultaneously become a powerful force for resistance.

On one hand, teaching can perpetuate cultural hegemony by reproducing existing power structures and narratives. Educational systems are deeply embedded in societal structures, and curricula often reflect the dominant culture’s worldview. This can result in the marginalization or erasure of minority cultures, reinforcing a singular narrative that aligns with the prevailing cultural hegemony. In this way, teaching becomes a tool for social control, as it shapes individuals to conform to established norms, perpetuating an unequal distribution of power.

Furthermore, teachers, consciously or unconsciously, may transmit biases that align with the dominant culture. Classroom dynamics, textbooks, and instructional materials may inadvertently promote stereotypes and perpetuate existing power imbalances. The reinforcement of certain cultural norms in educational settings can limit students’ critical thinking and inhibit the development of a diverse and inclusive worldview.

In this context, Priestly et. al’s (2015) model of the ecological model of teacher agency enables such cultural hegemony. In the practical-evaluative domain of the model, teachers’ ability to take action is always influenced by the specific context they find themselves in. This means the teachers are limited by the cultural, structural, and material resources at their disposal. Educators, armed with teacher agency to shape their teaching practices, can passively uphold existing power structures that perpetuate cultural hegemony. When teachers succumb to the status quo, reluctant to question ingrained biases within the educational system, they unwittingly contribute to the perpetuation of cultural hegemony. The lack of critical consciousness when exercising teacher agency for such instances hinders the potential for transformative education.

However, teaching can also be a form of resistance to cultural hegemony, challenging established norms and fostering a more inclusive society. Educators have the power to question and critique the dominant cultural narrative, introducing alternative perspectives that promote diversity and equity. By incorporating diverse voices and perspectives into the curriculum, teachers can disrupt the monolithic nature of cultural hegemony and empower students to think critically about the world around them. One instance where teachers can do this is by creating their own teaching materials that aim to challenge the dominant narrative manifested in textbooks or state-endorsed teaching materials and curricula (Giroux, 1997).

Furthermore, teaching can serve as a platform for advocating social justice and challenging systemic inequalities. Educators can instill in their students a sense of responsibility to question and resist cultural hegemony, motivating them to become agents of change. Through collaborative projects, discussions, and experiential learning, teachers can empower students to navigate and challenge the complexities of cultural dominance.

Concerning this, teacher agency becomes a catalyst for resistance when educators consciously navigate and challenge cultural norms. Freire’s (2000) concept of “critical pedagogy” emphasizes the transformative potential of education when teachers exercise their agency to cultivate critical consciousness among students. For teachers who have achieved teacher agency in the context of challenging cultural hegemony, teacher agency is manifested as educators strategically disrupt the dominant cultural narrative within the constraints of their specific educational context. By introducing diverse perspectives, questioning stereotypes, and creating inclusive learning environments, teachers exercise agency within the practical-evaluative domain, leveraging available resources to foster critical consciousness and resistance. This holistic understanding reinforces the idea that teacher agency is not a one-size-fits-all concept but is shaped by the dynamic interplay of cultural, structural, and material factors.

Moreover, in the context of challenging oppressive structures and promoting open dialogue, the ecological model of teacher agency recognizes that teachers are empowered by the resources available to them. The ability of educators as an emancipatory authority (Giroux, 1997) to actively challenge oppressive structures, encourage diverse perspectives, and create inclusive spaces is shaped by the cultural and structural aspects of their educational environment. In challenging oppressive structures, teachers exercise agency within the practical-evaluative domain, leveraging available resources to create a conducive environment for open dialogue and the exploration of alternative perspectives. This ecological approach to teacher agency reinforces the idea that educators play a crucial role in shaping classroom dynamics and interactions beyond the confines of curriculum decisions.

In conclusion, the dual nature of teaching—perpetuating cultural hegemony or serving as a form of resistance—is intricately tied to teacher agency. The choices educators make, enabled by the ecological model of teacher agency, determine whether they become agents of cultural reproduction or agents of transformative education. By recognizing and actively utilizing their agency, teachers can contribute to breaking down hegemonic structures, fostering inclusive learning environments, and empowering students to challenge and resist prevailing cultural norms.

References

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum.

Giroux, H. A. (1997). Pedagogy and politics of hope: Theory, culture, and schooling. Westview Press.

Priestley, M., Biesta, G.J.J. & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: what is it and why does it matter? In R. Kneyber & J. Evers (eds.), Flip the System: Changing Education from the Bottom Up. London: Routledge.

*This piece is solely the personal opinion of the author and does not necessarily reflect HIVE Educator’s stance.