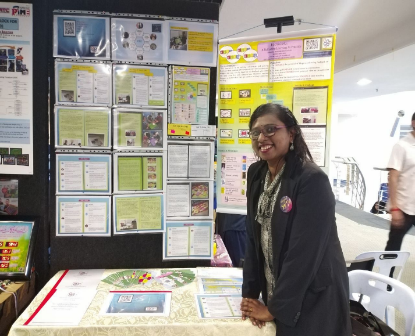

I am Madam J.D. Kumuthini Jagabalan, an English lecturer at Kolej Matrikulasi Kejuruteraan Kedah (KMKK). Over the years, I have been passionate about helping pre-university students improve their English proficiency, particularly in academic and critical writing. While my students are creative and analytical, many struggle to organize their ideas and write with coherence and depth. This inspired me to explore innovative methods that make writing both meaningful and structured.

My students, mainly from science and engineering streams, often show strong problem-solving skills in technical subjects but face challenges in expressing critical viewpoints in English. Their essays tend to be descriptive, lacking analysis and logical flow. This gap between creativity and structure motivated me to integrate Computational Thinking (CT) into writing instruction—an approach that aligns with the Post-Secondary English Language Curriculum Framework (PSELCF), which emphasizes organizing content, evaluating ideas, and writing coherent, detailed texts.

At the national level, my innovation supports the goals of the Malaysia Education Blueprint (PPPM 2013–2025) and the Higher Education Blueprint (PPPM (PT) 2015–2025), both of which stress higher-order thinking, communicative competence, and student-centered learning. In line with Wawasan Kemakmuran Bersama 2030, this initiative aims to equip pre-university students with critical academic writing skills to enhance inclusivity and educational equity.

CT, often linked to computer science, offers a structured way to approach complex writing tasks. Decomposition helps students break writing into smaller steps; pattern recognition enables them to identify common text structures; abstraction trains them to focus on key ideas; and algorithmic thinking guides them to follow logical sequences. For ESL learners, these skills make writing more organized and less overwhelming. Integrating CT principles allowed my students to plan, analyze, and structure essays more effectively while boosting their confidence and coherence.

This innovation aligns with 21st-century education priorities—problem-solving, creativity, and critical thinking (Bocconi et al., 2016; Tsarava et al., 2022). Writing became more than language practice; it became a cognitive exercise in decision-making and reflection (Bundy, 2007; Flower & Hayes, 1977). My lesson, Fairy-tale Venture, embodies this philosophy by merging creativity and CT-based writing instruction, contributing to SDG 4: Quality Education.

Issue in the Teaching and Learning (T&L) Process: In my pre-university writing classes, I observed that students often struggled to produce structured and critical writing. They could generate ideas but lacked the strategies to develop them into well-organized, analytical essays. Their writing tended to be descriptive with minimal reasoning or justification.

This issue became apparent in my study involving 46 engineering students—22 in Phase 1 and 24 in Phase 2. Initial writing samples showed that only about 28% demonstrated elements of critical thinking. Most essays were shallow, lacking argumentation and supporting evidence. These findings mirror past studies (Phakiti, 2018; Liu et al., 2015), which highlight that critical thinking is rarely taught explicitly in ESL classrooms.

I concluded that the absence of structured strategies to integrate CT into writing instruction was a key gap. Drawing on Anderson et al. (2001) and Ataç (2015), I recognized that higher-order thinking and analytical reasoning must be explicitly embedded in writing lessons. Thus, I aimed to explore how CT could help students approach writing as a problem-solving task.

The objectives of this study were twofold. First, it aimed to evaluate how students applied Computational Thinking (CT) principles—specifically decomposition, abstraction, and pattern recognition—in their writing following the intervention. Second, it sought to assess their ability to break down complex writing tasks and construct coherent narratives or arguments. Through this, the study intended to explore how CT could enhance students’ analytical and organizational skills in writing, ultimately fostering more structured and critical written expression.

Implementation

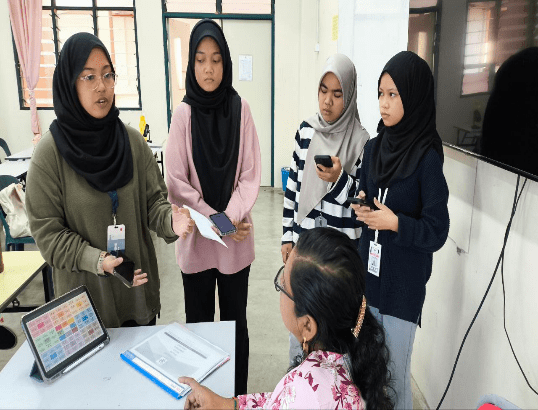

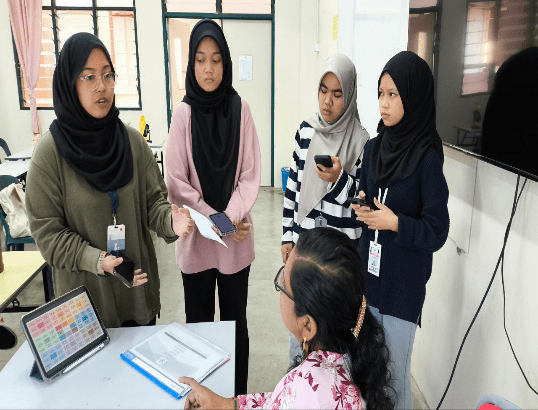

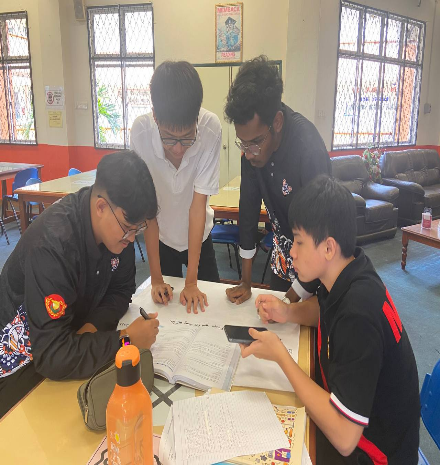

The first phase focused on introducing CT concepts and observing how students engaged with them. I began by explaining decomposition, pattern recognition, abstraction, and algorithmic thinking, and demonstrated how these applied to writing.

To make the lesson engaging, I used fairy tales such as Pinocchio, Little Red Riding Hood, and Hansel and Gretel as contexts for analysis. Students deconstructed these stories to identify core elements—characters, conflicts, and resolutions—before crafting their own versions. The activity aimed to help them break complex writing into smaller partand rebuild coherent stories.

Digital tools like Canva and e-books made the lesson interactive. Students created digital stories enriched with visuals, enhancing engagement. However, I noticed many struggled with abstraction: they included excessive details and found it hard to identify essential elements.

While decomposition was manageable, abstraction remained challenging. Post-lesson reflection revealed that students enjoyed creativity but needed more scaffolding and modeling. I realized that explicit guidance was crucial for applying CT effectively.

Based on insights from Phase 1, I refined the lesson with more scaffolding and visual aids. This time, I used new tales—Rapunzel and The Ugly Duckling—to maintain engagement and provide variety. I introduced graphic organizers to help students visualize story elements and guided them step by step in decomposing each story.

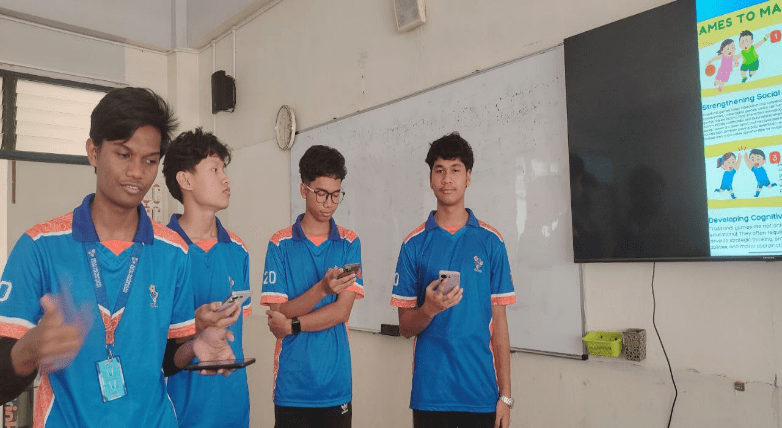

Group discussions encouraged peer collaboration and deeper engagement. The structured approach, along with visual tools, improved students’ focus and organization. Their rewritten stories showed clearer sequencing, stronger abstraction, and better logic.

Comparing both phases, students in Phase 2 displayed notable improvement. They were more confident and methodical in applying CT principles, and their writing reflected enhanced coherence. Still, abstraction posed difficulty for some, as they occasionally added irrelevant details. To address this, I conducted a short reinforcement session, asking guiding questions such as:

- What is the main problem the character faces?

- What actions move the story forward?

- Which details are not necessary?

I modeled the use of a graphic organizer with Rapunzel to help students identify key details and distinguish between essential and non-essential information. This focused activity enabled them to apply abstraction more effectively in their own writing.

Reflecting on Phase 2, I found it to be a turning point in my teaching—it highlighted the importance of explicit scaffolding, visual tools, and reflective practice in introducing CT to writing. Students became more engaged, confident, and strategic, viewing writing as a problem-solving process rather than a purely linguistic task.

Appendix

Lesson breakdown

Activity 1: Introduction to Computational Thinking (CT)

Objective: Introduce students to the concepts of computational thinking, focusing on decomposition, pattern recognition, abstraction, and algorithmic thinking.

- I reviewed CT principles briefly, emphasizing decomposition and abstraction.

- Students were provided with a character development graphic organizer to outline key features of their characters (e.g., personality, goals, obstacles).

- Students applied these principles by analyzing a fairy tale’s character and organizing the information in a character map.

Activity 2: Applying Decomposition to Fairy Tales

Objective: Students will break down a fairy tale into key components to better understand how stories are structured.

- Students formed groups and were given a set of abstracted story elements (e.g., a prince, a quest, a villain).

- They used a storyboard graphic organizer to plan the main plot points of their group’s fairy tale.

- As a group, students combined the abstracted elements into a cohesive story, using a flowchart to map out the major events.

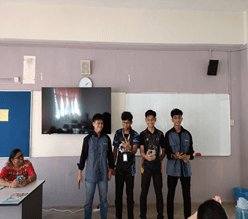

- They presented their stories to the class.

Activity 3: Writing an Original Fairy Tale Using CT Principles

Objective: Students will write an original fairy tale by applying CT principles, focusing on structure and key components.

- I introduced a writing scaffold template with prompts to help students structure their writing (e.g., setting description, character motivations, plot points).

- Students wrote their stories using the scaffold, ensuring that their work followed a logical sequence based on CT principles.

- Peer review was conducted with a focus on ensuring coherence and completeness of the structure

Graphic Organizer: Fairy Tale Analysis and Planning

| Story Element | Your Plan/Ideas |

| Title of Your Story | (Create an interesting title) |

| Main Character(s) | (Hero/heroine, magical creature, villain?) |

| Setting | (Place and time — magical forest, kingdom, etc.) |

| Problem/Conflict | (What challenge does the character face?) |

| Magic or Special Elements | (Magic spells, talking animals, enchanted objects?) |

| Key Events (Beginning) | (How will you introduce the character and setting?) |

| Key Events (Middle) | (What adventures or problems will happen?) |

| Key Events (Ending) | (How will you solve the problem? Happy ending?) |

| Moral or Message | (What lesson will your story teach?) |

| Story Flow Sequence (Algorithm) | (List the major events in order: Step 1 → Step 2 → Step 3…) |

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D. R., & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. Longman.

Ataç, B. A. (2015). The effect of higher-order thinking skills on writing development. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 191, 1334–1339.

Bocconi, S., Cesare, S., & Iannuzzi, D. (2016). Exploring the field of computational thinking as a 21st-century skill. EDULEARN16 Proceedings.

Bundy, A. (2007). Computational thinking is pervasive. Journal of Scientific and Practical Computing, 11(2), 121–132.

Flower, L. S., & Hayes, J. R. (1977). Problem-solving strategies and the writing process. College English, 39(4), 449–466.

Phakiti, A. (2018). Strategic competence in second language writing: The role of cognitive and affective factors. Language Teaching Research, 22(2), 199–218.

Tsarava, K., Kordaki, M., & Zacharia, Z. (2022). Computational thinking for enhancing the 21st-century skills. Computers in Human Behavior, 127, 106998.

Wu, T. T., Silitonga, L. M., & Murti, A. T. (2024). Enhancing English writing and higher-order thinking skills through computational thinking. Computers & Education, 213, 105012.

Student Writing Samples

Written by J.D. Kumuthini Jagabalan

Madam J.D. Kumuthini Jagabalan is an English lecturer at Kolej Matrikulasi Kejuruteraan Kedah. She is passionate about teaching and guiding students in developing their language proficiency, communication skills, and confidence. With a strong commitment to education and continuous learning, she actively contributes to academic programs, student activities, and research in English language teaching.