Introduction

Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) emphasizes not only the acquisition of content knowledge but also the cultivation of skills that enable learners to communicate complex ideas persuasively in diverse contexts (UNESCO, 2021; Rieckmann, 2017). While students often demonstrate theoretical understanding of sustainability concepts, they face challenges in articulating these ideas effectively in oral formats. To address this gap, product pitching activities provide a practical platform for integrating sustainability content with oral communication skills. The following sections outline best practices, grounded in findings and extended with insights, supported by detailed descriptions of the tasks conducted in the intervention.

Tasks

In practice, Tasks 1–3 focused on content mastery, persuasion, and structured communication; Tasks 4–6 targeted confidence-building, collaboration, and reflection; and Task 7 situated the entire project in a global, meaningful context. Together, they demonstrate how an integrated, multi-layered approach can transform students into confident communicators and socially responsible innovators.

| 1. Integrating Content and Communication |

| 2. Employing Authentic and Experiential Learning |

| 3. Utilizing Persuasive Communication Frameworks |

| 4. Addressing Public Speaking Anxiety |

| 5. Promoting Peer Feedback and Collaboration |

| 6. Embedding Reflection and Iteration |

| 7. Aligning with Global Priorities |

Task 1: Students designed sustainability-driven product prototypes applying at least three principles (reduce, reuse, recycle) and presented them orally.

The integration of content and communication proved highly effective when students were tasked with designing sustainability-driven product prototypes that applied at least three principles—reduce, reuse, and recycle—and presenting their ideas orally. Eighty-five percent of students successfully embedded these principles, demonstrating a strong connection between theory and practice. This experience showed that communication should not be treated as a separate skill but embedded within disciplinary learning. As students explained sustainability concepts aloud, they processed information more deeply, which strengthened comprehension and retention. While students initially relied on vague terms such as “eco-friendly,” guided practice helped refine their language. For example, one team improved their pitch to clearly state: “This packaging reduces single-use plastics by 40%, is made from recycled paper, and can be reused for storage.”

Task 2: A Product Pitching Challenge simulated entrepreneurial scenarios. Students pitched their sustainable innovations to peers and lecturers acting as investors.

Authentic and experiential learning was emphasized through a Product Pitching Challenge that simulated entrepreneurial scenarios. Students pitched their sustainable innovations to peers and lecturers who acted as investors, mirroring real-world professional practices. Seventy-eight percent of students improved in critical and creative thinking during this task. At first, many treated the activity as a typical classroom presentation, simply reading slides with minimal engagement. However, after rehearsal and feedback, they began using prototypes and storytelling techniques to enhance persuasiveness. One group introduced their biodegradable packaging through a narrative on local waste issues, making the pitch both engaging and realistic. This demonstrated how authenticity not only increased motivation but also gave purpose to classroom projects.

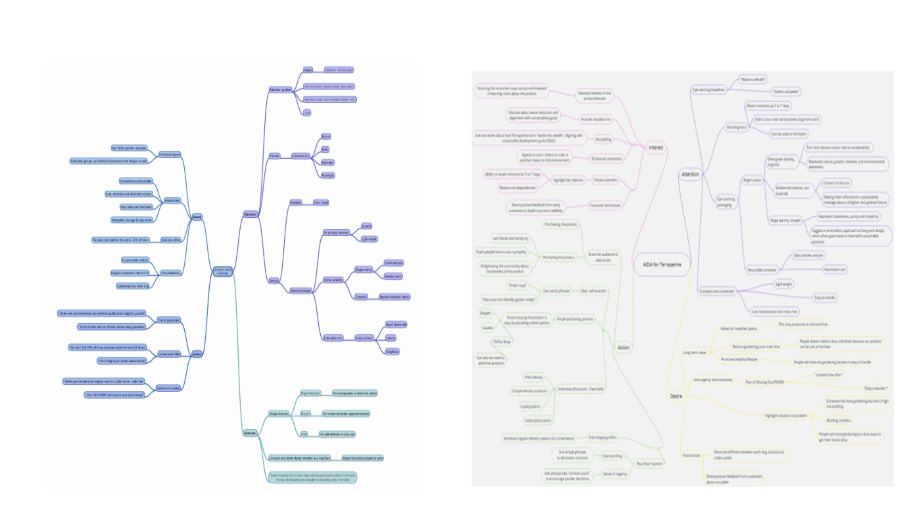

Task 3: Students were trained in the AIDA model (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action) and asked to structure their pitches accordingly.

To further support effective communication, students were introduced to persuasive communication frameworks, specifically the AIDA model (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action). This clear and memorable structure helped them frame their presentations persuasively while reducing cognitive overload. Ninety-two percent of students successfully applied the AIDA model, shifting from a simple focus on product features—such as “This bottle is reusable”—to persuasive framing like, “Imagine reducing 200 plastic bottles a year—this product helps you do exactly that.” This change highlighted how structured scaffolding can empower students to communicate more convincingly.

Task 4: Students practiced with mini-presentations in small groups, followed by mock pitches before the final round. They also used worksheets on voice control, pacing, and body language.

Addressing public speaking anxiety was also central to the process. Students practiced with mini-presentations in small groups before progressing to mock pitches and the final round. Worksheets on voice control, pacing, and body language supported their preparation. As a result, eighty-seven percent of students demonstrated increased confidence and fluency, using sustainability-related vocabulary with accuracy. Early sessions revealed nervous behaviours such as avoiding eye contact or over-reliance on notes. However, progressive exposure and supportive feedback helped normalize mistakes and encouraged growth. By the final pitch, many students spoke confidently without notes, engaging directly with their audience. One student reflected: “At first, I couldn’t even look at the audience. Now I can speak without reading, and I feel proud of that.”

Task 5: Teams completed peer feedback forms after mock sessions, giving constructive comments on clarity, persuasiveness, and delivery.

Collaboration was fostered through peer feedback, where teams evaluated each other’s clarity, persuasiveness, and delivery using structured forms. Students reported this process as highly valuable for refining their work. Initially, peer comments were vague, with remarks like “good job.” Over time, and with guidance, feedback became more constructive, such as “add statistics to strengthen your argument.” This shift encouraged negotiation, defense of ideas, and the integration of diverse perspectives, ultimately helping teams combine technical and social aspects in their product designs.

Task 6: Students wrote reflection logs after each practice pitch, identifying strengths, weaknesses, and plans for improvement. They revised their work for subsequent rounds.

Reflection and iteration further strengthened learning outcomes. After each practice pitch, students wrote reflection logs to identify strengths, weaknesses, and plans for improvement, revising their work accordingly. This iterative cycle mirrored professional practice, promoting adaptability and self-regulation. At first, reflections were superficial, such as “I need more confidence.” Later, they became more targeted and actionable, with comments like, “I must replace filler words with technical vocabulary and maintain five seconds of eye contact per section.” These reflections directly contributed to noticeable improvements in delivery and overall presentation quality.

Task 7: Each team linked their product explicitly to at least one Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) and articulated this connection in their pitch.

Finally, aligning projects with global priorities gave students a stronger sense of purpose. Each team was required to explicitly link their product to at least one Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) and articulate this connection during their pitch. This task enhanced ownership of their work and reinforced the idea that learning can contribute to real-world challenges. Early attempts were superficial, with statements such as “this supports SDG 12.” By the end, however, students provided more specific connections, for example: “This filter aligns with SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) by providing affordable, safe water to rural households.” Such articulation demonstrated not only a deeper understanding of global issues but also a growing sense of civic responsibility.

Conclusion

The integration of sustainability education with oral communication training through product pitching activities provides a powerful pedagogical model. Findings demonstrated measurable gains in students’ confidence, fluency, creativity, and persuasive ability. Beyond these outcomes, several insights emerged: communication and content learning are mutually reinforcing; authenticity fuels motivation; frameworks scaffold clarity; anxiety management is pedagogically essential; collaboration builds resilience; reflection supports adaptability; and global alignment fosters civic purpose.

Collectively, these insights affirm that best practices in sustainability education are most effective when they combine authentic application, structured support, and reflective learning. Such practices not only prepare students for academic success but also cultivate the competencies necessary for professional excellence and responsible global citizenship.

Written by J.D. Kumuthini Jagabalan

Madam J.D. Kumuthini Jagabalan is an English lecturer at Kolej Matrikulasi Kejuruteraan Kedah. She is passionate about teaching and guiding students in developing their language proficiency, communication skills, and confidence. With a strong commitment to education and continuous learning, she actively contributes to academic programs, student activities, and research in English language teaching.